来源 | 继民财经汇

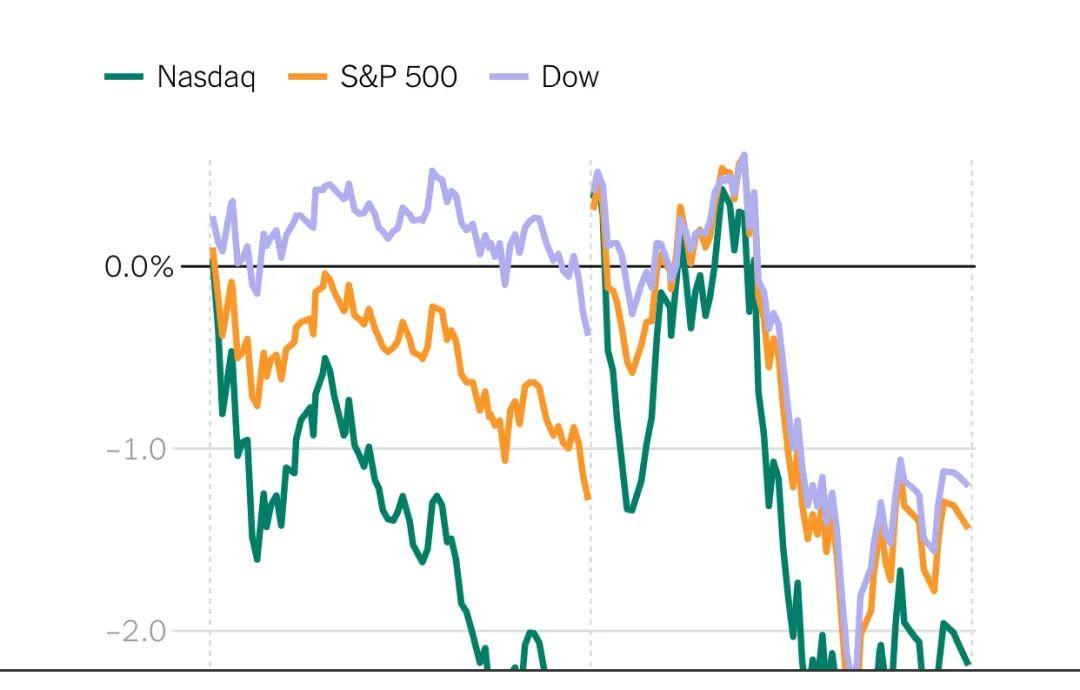

鲍威尔采访之后华尔街暴跌

美国股市周四大幅下挫,此前美国联邦储备理事会(美联储)主席鲍威尔未能安抚投资者,称美联储将继续控制公债收益率和通胀预期。

标准普尔500指数盘中大幅下跌1.3\%,收于3,768.47点,盘中低点为2.5\%。道琼斯工业股票平均价格指数下跌345.95点,至30,924.14点,跌幅1.1\%。蓝筹股基准指数一度暴跌逾700点。纳斯达克综合指数下跌2.1\%,至12,723.47点,增长类股领跌,涨幅居前。特斯拉股价下跌近5\%。

随着周四的大幅抛售,纳斯达克指数年内下跌1.3\%,转为负值。以科技股为主的上证综指盘中也进入了调整区间,较最近的52周高点下跌了10\%以上。

鲍威尔表示,经济复苏可能”对价格造成一些上行压力”,并重申美联储在改变政策前将”保持耐心”,尽管其认为通胀回升只是暂时的。

鲍威尔周四在《华尔街日报》(Wall Street Journal)就业峰会上说,他承认最近利率的快速上升引起了他的注意,但他说,美联储需要看到利率范围更广的上升,才会考虑采取任何行动。

在鲍威尔发表上述讲话后,10年期美国国债收益率跃升至1.54\%,近几周一直令投资者紧张不安。上周,10年期基准股指突然飙升至1.6\%的高点,引发股市大跌。在鲍威尔再次引发收益率飙升之前,收益率本周普遍回落。

鲍威尔没有强烈暗示美联储将改变资产购买计划以抑制利率的快速上升,这可能令一些投资者感到失望。越来越多的人预期美联储可能会像过去那样实施“扭转操作”,即出售短期票据,购买长期债券。

Vital Knowledge创始人Adam Crisafulli在一份报告中表示:“这是一个轻微的负面消息,因为他未能提供投资者所希望的那种令人安心的言论。”“对于如果美联储感到收益率升至过高水平将具体采取什么行动,他含糊其谈(他曾有几次机会支持改变量化宽松持续时间,但从未这样做过)。”

鲍威尔说,在几个季度或更长的时间内,物价高于美联储2\%的目标不会导致消费者的长期通胀预期发生实质性变化。

在鲍威尔的讲话中,金价下跌超过1\%,达到近九个月来的最低点。债券收益率的上升可能会削弱黄金作为通胀对冲工具的吸引力。

Bleakley Advisory Group首席投资官Peter Boockvar表示,“随着长期利率因他的评论而上升,我们再次看到市场正从美联储手中接管货币政策。” “美联储已经把自己置于一个艰难的境地,唯一的出路是如果通货膨胀没有进一步上升,没有达到2\%的目标。如果这样的话,他们就有问题了,因为如果他们仍然如此专注于就业,他们将不敢面对更高的利率。”

在数据方面,投资者消化了好于预期的一周初请失业金人数。美国劳工部周四公布,截至2月27日当周首次申领失业保险的人数为74.5万人,略低于道琼斯指数预计的75万人。

“(经济方面的)好消息对(市场)来说是坏消息,随着利率因经济成长改善预期而走高,股市受到了伤害,”独立顾问联盟首席投资官Chris Zaccarelli在一份报告中称。

一些人认为,进一步的刺激措施可能会给市场注入乐观情绪。参议院目前正在辩论众议院星期六通过的1.9万亿美元的救助计划。美国总统乔·拜登支持一项削减美国人获得经济刺激支票收入上限的计划。

以下是2021年3月4日鲍威尔接受华尔街日报专访全文(仅供交流)

NICK TIMIRAOS: Good afternoon. I’d like to welcome our audiences on Twitter and the WSJ home page and, of course, thank you to Chair Powell for spending time with us today. We’re really excited to have you join us.

JEROME POWELL: It’s great to be here, Nick.

MR. TIMIRAOS: So, to start, since December the outlook has brightened thanks to more vaccinations and the prospect of a lot more government spending. How have these developments changed your outlook for the economy and the labor market?

MR. POWELL: Nick, thanks. It’s great to be here today.

And if you’ll permit me, I actually want to start by noting that today is the birthday of Alice Rivlin, who was one of the real pioneers for women in economics and public policy. Alice would have been 90 years old day, she was vice chair of the Fed, founding head of the Congressional Budget Office, and held many other roles. A great person and a great leader. And I wanted to honor her today here on her birthday. How do I know this, you may wonder? And the reason is because she was a friend and she shared a birthday with my mother, who would have been 95 today. Another person of – you know, two women, actually, of integrity, intellect, and character. So if you’ll permit me, I will start that way. And now I will respond to your question.

So let me – let me start the answer by saying that Congress has given us two goals – maximum employment and price stability. And we have tools to achieve those. We’re strongly committed to achieving them. Before the – before the pandemic hit, we were very close to those goals. Unemployment was at a 50-year low, jobs were plentiful, wages were moving up, and inflation was also running close to but a bit below our 2 percent objective. That was a year ago now. Let’s look at where we are today.

The economy began to recover last May from the very sharp downturn at the beginning of the pandemic and made good progress through the beginning of the fall, let’s say. And then progress slowed sharply overall with the winter Covid spike, which reduced job creation for the last three months, through January, to about 29,000 a month, which is a drop in the bucket for an economy our size. So today we’re still a long way from our goals of maximum employment and inflation averaging 2 percent over time.

More recently, as you point out, we’ve got rising vaccination. We’ve got cases at lower levels. We’ve got strong support from fiscal and monetary policy. And while there are still risks, there’s good reason to expect job creation to pick up in coming months. And we need that, because we’re still 10 million jobs short of where we were – 10 million fewer people are working than were working when the pandemic hit. So it’s a lot of ground we have to cover. And those people are mostly in areas that are directly affected by the pandemic. That’s service industries, public-facing jobs.

I’ll also mention inflation, since that’s the other side of our mandate. We seek inflation that averages 2 percent over time. And we want that to happen because we want – because we want it to average 2 percent over time, we want inflation expectations to be anchored at 2 percent. And that’s really the goal.

So right now inflation is running below 2 percent, and it’s done so since the pandemic arrived. We do expect that as the economy reopens and hopefully picks up, we’ll see inflation move up through base effects, which means just that the very low readings of March and April will fall out of the 12-month window, and also through a surge, if you will, in spending that may come as the economy fully reopens. And that could create some upward pressure on prices. The real question is how large those effects will be and whether they will be sustained or more transitory.

And I’ll just say that for several decades the U.S. and the world, really, economy have been in a low-inflation world, and low inflation is what people expect both here and around the world. For those expectations to change, businesses and people would need to believe that larger increases in prices would be repeated year after year, and we think it’s unlikely that these deeply ingrained low inflation expectations would suddenly change.

It is more likely that effects like the ones I described would be one-time effects as the one- time effects of the fiscal boost fade. We have the tools to assure that longer-run inflation expectations are well-anchored at 2 percent, not materially above or below, and we’ll use those tools to achieve that end.

So that’s my thinking on the economy.

MR. TIMIRAOS: So I’ll get to inflation in a second. But on employment, you know, when people are vaccinated, when they’re able to go travel and feel comfortable seeing their family again, there could be a big pickup in activity. Does that mean employment could get back to where it was before the pandemic sooner than you previously thought?

MR. POWELL: Well, the answer is I would hope so.

So let me tell you how we define maximum employment. People focus on the unemployment rate, but it’s really much broader than that because if you haven’t looked for a job in the last four weeks then you’re not counted as unemployed. You’re counted as out of the labor force.

So if you look at those who have left the labor force since the pandemic and also those who are unemployed, then you get a very large number of people who are around the edges of the labor market and should be thought of as generally people who want to go back to work. It will take some time to get back to maximum employment. It took us many years to get there before. And that’ll really just depend on how strongly the economy picks up once we do get past the pandemic and once economic activity picks up and hiring picks up.

Again, there’s a lot of ground to cover to get – to get back to what I would call maximum employment. We want to see wages moving up. We’d want to see that the gains in employment are broad-based and that different demographic groups were experiencing it. So we have a high standard for identifying what maximum employment is, and we’ll – we think it’ll take some time to get there. But that is exactly the state we’re trying to achieve, and we’re trying to achieve it, you know, as quickly as we – as we possibly can.

MR. TIMIRAOS: So just because we hit 4 percent unemployment, for example, if labor- force participation was still low relative to where it was last February, does that mean we’re not at maximum employment?

MR. POWELL: Yes. I mean, we’ll look overall at a range of indicators, and certainly the unemployment rate and the labor-force participation rate are two key ones. It’s actually even broader than that. But certainly, labor force – we’ve had the sharpest drop in labor- force participation in many decades coming out of the pandemic, and that just means that there are quite a few people who are technically out of the labor force but were working in February.

So some of them will have retired, but the vast bulk of them actually want to go back to work – but they’re not currently looking because perhaps the business where they worked is still temporarily closed or permanently closed. So the answer is yes. Four percent would be a nice unemployment rate to get to, but it’ll take more than that to get to maximum employment.

MR. TIMIRAOS: And do you think we could get there this year?

MR. POWELL: No. I think that’s highly unlikely. I think we have significant ground to cover. When you think about it, if you add back in – a broader measure of unemployment is about 10 million people. I’m hopeful that we can begin to make good progress again, that hiring will pick up.

So as I mentioned, hiring was strong during much of last year after the – after the critical phase of the pandemic in March and April, but it really slowed down over the winter with the spike in Covid cases and it hasn’t – we don’t – we don’t think it’s really picked up much yet. We’re looking for that to happen as cases come down, as vaccinations increase; hasn’t happened yet. So I think it’s not at all likely that we’d reach maximum employment this year. I think it’s going to take some time to get there.

MR. TIMIRAOS: Let’s talk about inflation for a second. Between the $900 billion the Congress approved around Christmas and then this $1.9 trillion package Congress is looking at right now that’s some serious spending, and the market has been pushing up longer-term interest rates maybe because it seems to anticipate an unwelcome increase in inflation. Is the market wrong?

MR. POWELL: Well, is the market wrong? That’s a pretty broad question, I would say. Maybe to be a little more specific, let me talk about the sort of – market pricing I think is what you’re really asking about.

So in terms of the bond market, so you’re right, bond market rates moved up. And as far as that is concerned, a number of factors are factored into it. But from our perspective, we monitor a broad range of financial conditions and we think that we’re a long way from our goals. We think it’s important that financial conditions support the achievement of those goals, and I would be concerned by disorderly conditions in markets or a persistent tightening in financial conditions that threatens the achievement of our goals. I would be concerned if those things were to happen.

In terms of – the other question tends to be markets reflect an estimate of when we would raise interest rates, and so let me – let me talk about that. That’s the other question. So the question is, what would it take for us to want to raise interest rates? Right now our policy rate is at – effectively at zero.

So we have a new framework, and we’re strongly committed to implementing that framework, and we have guidance out to implement that framework. As I mentioned, with rising vaccination and other things happening – fiscal policy support – there’s good reason to think that the outlook is becoming more positive at the margin and in coming months we could see spending and job creation picking up.

So let me talk about the guidance. By the way, the guidance is always – it’s outcome-based. It’s not date-based. So we never – we never think – we never say, hey, we’re going to do this in 18 months or 24 months. It’s always when these conditions are fulfilled.

So for asset purchases, as you’re aware, we say that they will continue at least at the current level until we achieve substantial further progress toward our goals. That’s actual progress, not forecast progress. And as I mentioned, there’s good reason to think we’ll begin to make more progress soon. But even if that happens, as now seems likely, it will take some time to achieve substantial further progress.

For interest rates, to raise interest rates above zero, very simply, we said we’d want to see labor market conditions consistent with our assessment of maximum employment, and that means all of the things that we – that we talked about. We’d want to see inflation sustainably at 2 percent and we want to be on track to have inflation run moderately above 2 percent. So these are highly desirable outcomes that we – that would represent an economy that’s very far along the road to recovery, and there’s just a lot of ground to cover before we get to that.

The last thing I’ll say is this, and I want to be clear about this. If we do see – as I mentioned, if we do see what we believe is likely a transitory increase in inflation where longer-term inflation expectations are broadly stable at levels consistent with our framework and goals, I expect that we will be patient.

MR. TIMIRAOS: So there’s a lot there. Thank you for that. I guess, you know, the question is, has the recent run-up in bond yields been consistent with your economic outlook and with the new framework that you’ve adopted that takes a more relaxed approach to inflation?

MR. POWELL: You know, I don’t want to be the judge of a particular level of one interest rate among many, one asset price if you will among any. Our new – for your – the people at your conference benefit, our new framework says that we will seek inflation that runs moderately above 2 percent for some time after we’ve had a shortfall of inflation. And it also says – it commits us to not raise interest rates just because the labor market gets strong. And those things, I think, will – you know, will be good for the labor market over time.

So, again, I would just say as it relates to the bond market, I’d be concerned by disorderly conditions in markets or by a persistent tightening in financial conditions broadly that threatens the achievement of our goals.

MR. TIMIRAOS: And I understand why you wouldn’t want to comment on a specific level of rates, even if the level of rates isn’t a problem. Was the speed with which real rates adjusted over the last week problematic, in your view?

MR. POWELL: You know, it was something that was notable and caught my attention. But again, it’s a broad range of financial conditions that we’re looking at, and that’s really the key. It’s many things.

And we want to see, and would be concerned if we didn’t see, disorderly conditions – orderly conditions in markets, and we don’t want to see a persistent tightening in broader financial conditions. That’s really the test. It’s not appropriate to isolate one particular interest rate or price. It’s more of a broader assessment that we make.

MR. TIMIRAOS: I guess what I’m wondering is the market now believes the Fed will raise rates earlier and faster than it thought a week ago. Are you saying that’s consistent with your outcome-based policy guidance and with your new framework?

MR. POWELL: That’s going to entirely on the path of the economy. So I laid out the conditions upon which we would consider raising interest rates. And that’s labor market conditions that are consistent with maximum employment – which is – you know, that’s a big thing to get to. And it will take some time to get there, right? Inflation sustainably at 2 percent, and inflation on track to run moderately above 2 percent for some time.

So those are the conditions. When they arrive, we will consider raising interest rates. We will not – we’re not intending to raise interest rates until we see those conditions fulfilled. So it’s really going to – the timing will depend entirely on the fulfillment of those conditions. And as I said, again, you know, if – I’ve told you that we are – we think we’re likely to see inflation move up during the course of this year, to really two things. First, the base effects I mentioned, but also just kind of reopening effects where businesses will be potentially hit by a lot of demand as the economy recovers, which is a good thing. But you could see bottlenecks. You could see prices moving up.

We’re inclined to see those as transient. And it’s the difference between a one-time surge in prices and ongoing inflation. Ongoing inflation, where prices go up year, after year, after year tends to happen when people’s psychology becomes that they believe that that’s what will happen, and then have no faith that the central bank, frankly, will prevent that from happening.

So, as I’ve said our – you know, the key thing is to keep longer-run inflation expectations anchored at 2 percent. If that happens then a transient increase in inflation will not affect inflation over a longer period. And we intend to use our tools to keep inflation expectations anchored at 2 percent, which gives us the ability to do all the things we do when the economy is weak.

MR. TIMIRAOS: It could take months, though, for the data to contradict or validate this narrative about transient inflation. And obviously investors are twitchy right now. Do you think your guidance is too vague right now to be properly understood by investors?

MR. POWELL: I’m trying to make it as clear as possible. And I went though, you know, the guidance – I think the guidance for tapering asset purchases has an element of judgment in it. But I’ve also said that we will, well in advance of any decision to consider tapering asset purchases, we’ll communicate about our sense of progress toward substantial further – toward the goal – substantial further progress toward our goals. So we’re not looking to surprise people with that.

And as far as – as far as the – you know, the rate liftoff guidance, it’s pretty specific. And as I said, it will take some time to get there, if you think about it. You got to – you got to have a very strong labor market and inflation performing in line with our – it’s a picture of an economy that is all but fully recovered, you know, so – and, you know, the sooner that happens the better. But I would say realistically, that’s going to take some time.

MR. TIMIRAOS: And as we sit here today do you think the hope of a brighter outlook you’ve discussed here might lead to substantial further progress being met, being achieved this year?

MR. POWELL: Again, so I’m – I’ve been – so far been able to not reduce it to an estimate of time. I mean, that will come, I think, when we – when we see – when we can see that. Right now – right now we haven’t been making much progress. I mentioned 29,000 jobs per months for the months of November, December, and January. So and spending was maybe a little better than that, but in the job market you saw real – a real slowdown in job creation. That wouldn’t get you to maximum employment anytime soon. You know, that would – that’s just not enough.

So I do expect, and many forecasters expect, that there’ll be a pickup in job creation. We’ll have to assess that when it comes. I don’t want to be making – but, again, I think realistically though it’s March. And, you know, we’re going to start – presumably in the next couple of months we’ll start to see stronger employment. And we’re going to want to see substantial further progress in both maximum employment and stable prices.

That’s going to take some time. It just will take some time because, you know, you’d had three months now where you didn’t make much progress. So we’ve got to get going and start making it again, and for us to assess that and signal forward it’s going to take some time.

MR. TIMIRAOS: As you noted, the Fed is buying $120 billion per month in Treasury and mortgage securities. You’ve been saying for the year – for the past year that your asset purchases are designed to support market functioning.

Have you seen anything in the Treasury market that suggests a need to lengthen the maturity profile of your purchases?

MR. POWELL: We think our current policy stance is appropriate. As I mentioned, the federal-funds rate is at the effective lower bound, which is our technical name for zero or close to zero. We’ve provided really strong guidance about the conditions we need to see before we’d consider raising it.

We’re buying $120 billion in Treasurys and mortgage-backed securities across the curve, and we’ll continue at least at that pace until we see substantial progress toward our goals. Financial conditions are highly accommodative and that’s appropriate, given the ground that the economy has to cover. It’s always the case that if conditions do change materially the committee is prepared to use the tools that it has to foster achievement of its goals.

MR. TIMIRAOS: Well, and if there were some kind of rate move that you felt represented a threat to your outlook, what would you do to address it?

MR. POWELL: Well, that’s sort of a hypothetical situation. You know, we would use our tools – it’s hard to say in the abstract, but we would use our tools as appropriate to foster the achievement of our goals.

MR. TIMIRAOS: There’s been some discussion in recent days that’s gotten a lot of attention, the idea of selling bills or letting bills run off of your portfolio to address a collateral squeeze in money markets. Is that something you think needs to be considered at this time?

MR. POWELL: Nick, you know, as I said, I wouldn’t want to speculate. Really, I’ll just say if conditions do change materially we’ll be prepared to use our tools in whatever way is appropriate at that time to foster the achievement of our goals.

MR. TIMIRAOS: I know a lot of this talk about inflation and interest rates can feel abstract, and so I wonder if you could put into plain language what the practical effect is of the changes the Fed has been making over the last year to your framework. What does it mean for everyday workers?

MR. POWELL: Great question. So I guess I have to say, for a long time and when I was entering the job market years ago, when we had low employment we had high inflation. So when the job market got good and tight – employers were, you know, actively seeking people and there were plenty of jobs – inflation would be moving up and, therefore, the central bank – the Fed – would be raising interest rates to cool off the economy, and I would say 50 years ago that was appropriate because there was this tight connection between unemployment and inflation.

More recently, though, I think the Fed established its credibility several decades ago on inflation and since that time the connection between, you know, having a lot of people out of work and inflation under control has gotten very, very weak. So our new framework very explicitly takes that under – takes that in, that new learning, that new understanding, and says that we won’t raise the interest rates to cool down the economy just because unemployment gets lower, just because employment gets high.

We’re going to wait to see signs of actual inflation or the appearance of other risks that could threaten the achievement of our goals. And we’ve seen that the economy can sustain very low levels of unemployment without inflation.

So what does that mean for job seekers? It should mean that, you know, the job market will be stronger over time. We also saw the terrific social benefits of a very strong job market during 2018, ’19, and the early part of ’20. We saw workers at the low end of the wage scale getting the biggest increases.

We saw labor-force participation moving up, so people who might have given up on finding a job found a job and people at the margins of society, maybe coming out of prison, things like that, got jobs. And it was – there was really a lot to like about our very strong labor market.

So, you know, we’re really, really committed to getting back to a very strong labor market and, you know, the strong anchoring of inflation expectations, the inflation dynamics that we have, give us the ability to do that. But it does require that we remain committed to keeping inflation expectations anchored at 2 percent, and we will do that.

MR. TIMIRAOS: Of course, some prominent economists in the last couple weeks – as you know, Larry Summers, Olivier Blanchard – are saying that policy makers have maybe grown too quick to conclude from recent decades that low employment is no longer inflationary. Are they right to worry about this right now?

MR. POWELL: Well, so many people, particularly people who are now entering the job market, will not have lived through high inflation. And high inflation is a very bad state of affairs. And it hurts people the most on fixed incomes and lower incomes, who have less wealth to draw upon. So that would – inflation was very high when I was in college and coming into the job market. So it’s really not something we want.

But I would say, you know, at the – at the Fed, we are well-aware of the history and how it happened, and not going to allow it to happen again. It was a situation where the Fed didn’t step in when it should have, when inflation pressures were building. Not at all the current situation. Inflation is currently running below 2 percent. It’s running at 1 1⁄2 percent. But we’re very mindful of what happened in really the 1960s and 1970s and, you know, determined not to repeat that mistake.

But you have to differentiate though between one-time price effects – such as things that happen around the reopening of an economy, not something we have much experience with, and just the sort of – now, when I say base effects, that’s a technical term. But you look through that, it’s not really signaling anything about inflation. So, I mean, we’re very mindful. And I think it’s a constructive thing for people to point out potential risks. It’s always constructive. I always want to hear that.

But I do think it’s more likely that what happens in the next year or so is going to amount to prices moving up but not staying up, and certainly not staying up to the point where they would move inflation expectations materially above 2 percent. That would take – the public would have to come to believe that that’s the new policy, that’s the new reality. And I really don’t think that, you know, a couple of quarters of prices, or even more than that – but prices being above 2 percent would change the psychology.

Particularly in a world where inflation has been the problem for the last decade in all of the major advanced economy countries. They’ve been facing low inflation because of these global disinflationary pressures, which haven’t gone away, and they’re not going to go away overnight.

MR. TIMIRAOS: So it’s been a year, really, since we began to face this pandemic, at least in the United States. You announced your first of two emergency rate cuts a year ago yesterday. And so as we mark that anniversary, what are one or two of the most important lessons you think we’ve learned from this economic crisis?

MR. POWELL: Yeah, we’ve been thinking about that a lot. We’re sort of going into the anniversary of that extraordinary period. So the first thing is – and we really implemented something that we learned from – in the last crisis, the global financial crisis. And that is that we needed to move quickly and powerfully with our tools, and not hesitate. And we really did that this time. And so did Congress, by the way.

The Cares Act passed in late – within a month really of the pandemic starting to get going we had very strong fiscal policy in the original Cares Act unanimously passed by Congress. And we cut rates twice. We started asset purchases to support market function at an unprecedented level. And we also announced the opening and opened facilities to replace – to assure that the flow of credit to households, businesses, and municipalities in the country. All of those things were in place very quickly.

So thing one is when you have a real crisis, attack quickly and use – don’t hold back. Thing two is don’t stop until the job is done. So there’s a real sense that in the last crisis really fiscal policy pulled back and became tight, and it led to a very long, slow recovery. So we’re committed to using our tools and, you know, staying on the playing field with our tools until the job is really done. We’re committed to that. And Congress, of course, has come with quite strong fiscal policy.

And so I think, you know, we’re in – you know, if you look around, the place where we’re in now, there’s still a lot of pain out there and more than a half a million people have lost their lives to the pandemic.

But compared to the economic scenarios that we were contemplating a year ago, this is – you know, it’s good to be where we are, and particularly with the vaccines now. No one thought we’d have vaccines within a year – less than a year, and now vaccination is moving at a good pace. We really are looking – if we can just decisively end the pandemic, we could get back to normal and avoid a lot of the longer-term damage that we were concerned about happening. But we haven’t done it yet.

We haven’t succeeded in this yet, but we are – we’re right there. I think there’s – if we can – the next couple of months will be very important on the – on the pandemic. If we can keep making progress, that’s what will help the economy more than anything.

MR. TIMIRAOS: And of course, last year you talked a lot about the need for fiscal policy – that is, government spending – to engage. It came through at the end of the year with $900 billion. Now it looks like we may get something, you know, a few shakes less than $2 trillion. Is this going to be too much – too much too fast?

MR. POWELL: You know, we – it’s not our job. We are – our job, as assigned by Congress, is to use our tools to foster the achievement of maximum employment and price stability. We’re not the Congressional Budget Office. We don’t make assessments of – and we don’t play a role. We’re not up in Congress testifying on this or that fiscal policy. We’re not in the discussions or in the negotiations. It’s just not our job.

So I wouldn’t comment on this particular fiscal policy. It’s just not – it’s just, you know, we have this precious independence, the Fed does, from political interference in our decisions. And you know, the other side of that is stick to your job, stick to your knitting, which we try to do.

MR. TIMIRAOS: Yes, we’ve heard that from you a few times before.

Since we are here talking about jobs and careers, you said recently that you love your job and your term as chair is up in less than a year. Would you like to serve a second term if it was offered?

MR. POWELL: So, again, I have nothing for you on that today. My focus is on, you know, the current challenges that we face and doing my job. There’s a lot left to do. We have a lot of ground left to cover and good reason for optimism.

I mean, the last thing – the last maybe lesson would be even if terrible times try to take counsel from your hopes as well as your fears. Because, you know, when – in March and April of last year, I mean, you know – but you saw the way that people responded and the way – you know, the response and then where we are, it’s really – we should never sell ourselves short. And so I would just point out that it’s good to be optimistic. But nothing new for you on the – on that topic.

MR. TIMIRAOS: Well, on that note we look forward to the day when we’re able to have events like this in person again. But notwithstanding that, we’re honored to have had you join us virtually today. So thank you, Chair Powell, for a great conversation.

MR. POWELL: Thank you, Nick.

MR. TIMIRAOS: And also, thanks to our audience following online at WSJ.com and on Twitter.

来源 | 继民财经汇

中概股美国上市(2021年1-2月):上市13家,募资近24亿美元